At Home and Abroad

By Sam Adams

February 16-22, 2006

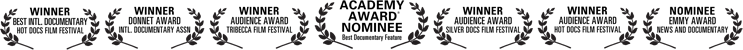

Hear the phrase "human rights" and your mind immediately goes some place else. But the most striking documentaries in this year's Human Rights Watch International Film Festival could've been shot around the corner—and one of them was. The dirty politics on display in Marshall Curry's Street Fight -- media suppression, government intimidation, voting irregularities—are the kind of thing you'd shake your head over if it happened in some banana republic. But as it happens, Curry's Oscar-nominated documentary takes place during the 2002 mayoral race in Newark, N.J.

Street Fight's combatants are four-term incumbent Sharpe James and soft-spoken but determined challenger Cory Booker, a 32-year-old city councilman. Apart from Booker's contention that James has enriched himself while ignoring the city's high crime rate, Curry largely glosses over both sides' rhetoric, focusing instead on the bare-knuckle tactics James uses to cut his opponent off at the knees. Police try to ban Booker from canvassing a public housing project, while his supporters report a campaign of harassment from city officials: licenses revoked, contracts threatened. Curry himself is manhandled every time he gets near the mayor, prevented from videotaping a public debate and ordered to turn over his tapes by a man who identifies himself as a police officer but won't show his I.D. (Curry refuses.)

As the campaign heats up and Booker starts to pose a real threat, James stoops ever lower. At first, it's just a matter of disinformation, exaggerating Booker's war chest threefold to portray him as a tool of special interests. But when James plays the race card, things get spectacularly ugly—no less because both candidates are black. James, a self-identified "poor boy from Howard Street," paints Booker, a Rhodes scholar with degrees from Stanford and Yale Law, as a moneyed "carpetbagger"—never mind that Booker's parents were working-class veterans of the civil rights struggle, or that he went to Stanford on a football scholarship. James is quoted calling Booker a "faggot white boy," and on the Today show refers to him as "Jewish." In essence, James sets out to convince Newark's working-class black voters that Booker is not one of them—and if he has to appeal to homophobia or anti-Semitism to do it, so much the better.

Too late, the national media start to take an interest in the race, and black celebrities flood into town to lend their support. Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson put their weight behind James, while Spike Lee and Cornel West stump for Booker—a split that vindicates Curry's claim that the race serves as a referendum for the future of black leadership in America. Booker's defeat, by a heartbreaking 3,500 votes, ends the film on a devastating note, but the real postscript is yet to be written: As promised, Booker announced his 2006 candidacy last week, while James remains tight-lipped about whether he'll seek a sixth term.

Set half a hemisphere and two decades away, Pamela Yates' State of Fear nonetheless resonates at home, even if Yates' framing voiceover lays the parallels on too thick. At base, Yates' film, drawn from the records of Peru's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, is the story of a society that sacrifices everything to combat terrorism, and ends up no safer for it. Riven by racial, economic and geographical divides, Peru was ripe for the insurrection of Shining Path, led by university Maoist Abimael Guzmán. But Shining Path did as much harm to the indigenous people they were supposedly liberating as their ostensible enemy, conducting mass executions and turning abducted children into merciless soldiers. (One, now grown, says that once you start killing, it becomes "an addiction, like giving a kid candy.") The government response was as self-defeating, and even more lethal: Tens of thousands of Peruvians were murdered by the state under the presidency of Alberto Fujimori, who dissolved Congress, paid off the press (shown accepting piles of cash) and imprisoned or killed his opposition. Even after Guzmán was captured and Shining Path dissolved, Fujimori maintained his campaign against invisible terrorists, mainly as a way of protecting his power and lining his pockets. If that sounds familiar, it's supposed to—Yates has clearly structured her film as a cautionary tale to the U.S. and the rest of the world about the costs of the war on terror. (Its overreaching subtitle is "The Truth About Terrorism.") Yates is too concerned with delivering an illustrated lecture to make State of Fear dramatically compelling—even if it doesn't name names, the fictionalized thriller The Dancer Upstairs imparted a better sense of how a nation can be gripped in revolutionary madness. But if Yates doesn't entirely make her case, State of Fear still provides sobering food for thought.

The parallels in Justice, Maria Ramos' observational portrait of Rio de Janeiro's court system, are almost too strong: The movie offers little that can't be seen in Frederick Wiseman's Domestic Violence or Raymond Depardon's 10th District Court. The most effective sequences catch a judge, a prosecutor and a defense attorney dining with their respective families, discussing the day's cases in radically different but equally conversational terms. Helen Klodawsky's No More Tears Sister: Anatomy of Hope and Betrayal tells a story similar to State of Fear's, but focused through the experience of two sisters: Nirmala Thiranagama, a former militant in Sri Lanka's Tamil Tigers, and her sister Rajani, a radical activist who was converted to human rights causes and murdered in 1989.

Human Rights Watch International Film Festival Through Sun., Feb. 19 International House

View on Philadelphia City Paper's website

Back to Press

© 2012 Marshall Curry Productions. All rights reserved.